A symposium on crafts: Lin Cheung celebrated in style

Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam – November 10th, 2019 | by Saskia van Es

British jewellery maker Lin Cheung is the twentieth recipient of the Françoise van den Bosch Award. A symposium was held in her honour: The Relevance of Crafts. Lin Cheung herself contributed with three special jewellery interventions. Theory and a sensory experience made for a noteworthy combination.

Françoise van den Bosch Award winner Lin Cheung giving her acceptance speech, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam. Photo: Zhi-Lang Wang

Words and jewellery

Over the years, the biennial Françoise van den Bosch Award has been presented to jewellery makers of international standing. Often the ceremony coincided with the opening of an exhibition of the makers’s work. This time around, the Françoise van den Bosch Foundation organized a symposium, in cooperation with the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam. The reason behind this choice was the conceptual character of Lin Cheung’s work. Her jewellery pieces manage to address substantial issues in society. To reflect on this critical ability of crafts, three thinkers were invited: Grant Gibson, Juliette Huygen and Jan Boelen. What is relevant in the relationship of both makers and consumers to material and objects? On a Sunday afternoon last November, the contemporary jewellery world gathered in the auditorium of the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam to find out.

A member of the audience, part of the ‘live exhibition’, wearing Lin Cheung’s pendant in front of Jewellery Library installation by Lin Cheung in the library of the Stedelijk Museum, on view during November and December 2019. Photo: Zhi-Lang Wang

Stone carving offering a renewed freedom

The artist herself presented a temporary installation in the library of the museum, Jewellery Library. Among the ‘real’ art books there was a shelf with white sleeved, fictitious books on jewellery. Actual jewellery of her hand was present as well during this afternoon. A group of colleagues and friends wore her pieces, mingling with the crowd. In a glass case sat the counterparts of the pieces: 34 specially made mother-of-pearl pendants in the shape of museum labels, reading ‘jewellery unavailable’ or ‘jewellery on loan to the audience’. Besides this, Lin Cheung presented the audience with a booklet containing images of recent work and a few short, eloquent artist’s statements. Her jewellery has always explored the relationship with things people care about in a shifting society. Recently Cheung carves most of her work in stone. This skill, or rather, craft, she only learned in 2014. As a consequence, she gained a renewed sense of freedom in her making process: ‘Stone carving is slow. And unpredictable. This relative slowness and uncertainty prompted a sustained meditation on particular ideas.’ With these words in mind, The Relevance of Crafts as the theme was an apt departure for a symposium in her honour.

Show case with 34 ‘museum labels’ referring to removed exhibits, being worn by members of the audience, installation made for the afternoon of the symposium. Photo: Maarten Nauw

How craft no longer became a dirty word

Writer Grant Gibson’s name is almost synonymous with crafts. Gibson guided his audience through the recent popularity of craft in the UK, the environment in which Lin Cheung’s work originated. The keynote speaker had a lot to share in little time (one of the listeners regretted afterwards that this was not one of Gibson’s successful Material Matters podcasts, so she could have slowed down the speed to 50%).

In the UK in the early 2000s crafts were something particularly uncool, according to Gibson. Brown pots and wicker baskets seemed to be in the way of modern design. The license to use craft without sneers was propelled by some recent events. First of all, Richard Sennett’s 2008 book The Craftsman was pivotal. Here was an authority pointing out that we are all surrounded by craft, and we better pay respect to it. More books were to follow, by Edmund De Waal for example, with personal stories of a maker taking on big societal topics. The art world came to embrace craft, continued Gibson, and Grayson Perry, a potter, made it to the Turner Prize. Politicians and multinational alike saw the advantage of being associated with craft – for a hint of authenticity. Kettle Chips ‘were apparently lovingly crafted’ and McDonald’s commissioned a paper-cut artist for a campaign. Although it looks like everything is rosy now, Gibson sees issues of concern. He points out a parallel to the 1970s when DIY and ecological self-sufficiency blossomed, only to be replaced by a Wall Street mentality in the 1980s. Now, ten years after Sennett’s book, another book title is dominating the debate: Glenn Adamson’s Fewer, Better Things. Gibson left us on an optimistic note: this ecological and sociological thinking, that what Adamson calls ‘material intelligence’, gets more ingrained in how we produce objects and food. If we decide to produce them at all.

A call to fetishise shine

After this extensive background of the coming of age of crafts, Juliette Huygen, a Dutch jewellery maker, illustrator and a material culture researcher, turned to the concept of shine. To determine whether shine in our days is a sign of superficiality or not, she made pit stops at the disciplines of anthropology, psychoanalysis and philosophy. Huygen peppered her academic narratives with well researched images and videos. Jewellery has always served to ‘reflect and protect the wearer’, she set out. What it has in common with the early bead money, shell money to gold and diamonds – it all shines. Before you regard that as only showing off, she said, think of shine as something that also brings you closer to spiritual light. For psychoanalysts, Huygen argues, it all starts early in life, when people form intimate relations with objects to help to decipher the world and the ‘I’ in it. That first ‘transitional object’ as it is called, a comforting thing such as a blanky for example, is taken everywhere and it provides protection. Here you go, a primary form of an amulet, a primary form of jewellery. To carry around a shiny object – or a mobile phone for that matter – reminds us of our identity. Huygen used the word ‘memento vivere’. Imagine the crowd that afternoon, each wearing their mementos to live life. Uplifting isn’t it? Huygen illustrated these words with images of hip-hop artists and rappers, their personas created by ostentatiously displaying shine and bling. The cultural value of their outfits – both a call for attention, a shield of protection and a device blinding visibility – cannot be underestimated. Therefore, Huygen invites her audience to ‘positively fetishise shine’. With, of course, ‘jewellery remaining the perfect medium to do so’.

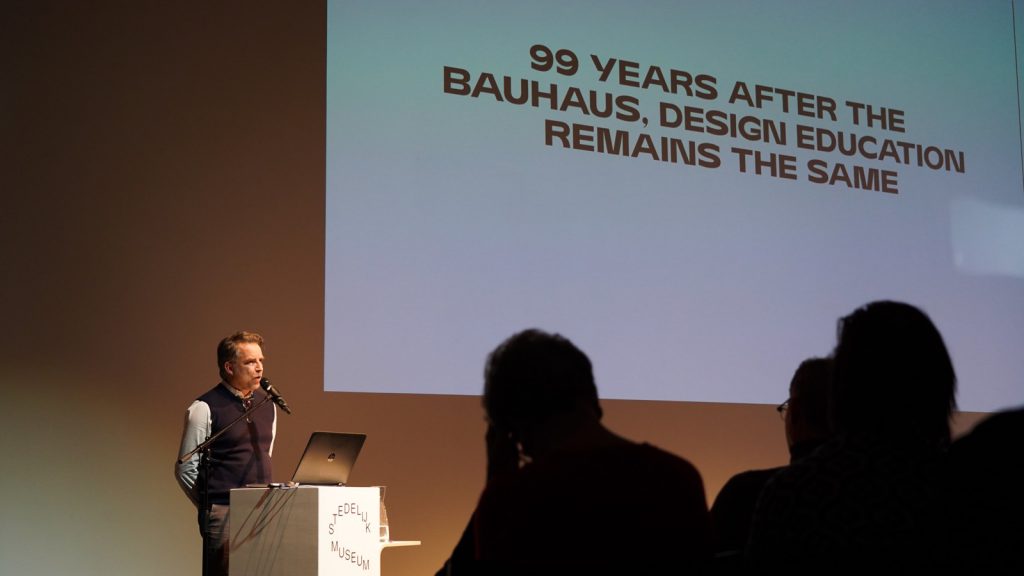

Speculative design manifesto

From fashioning ourselves the programme proceeded to fashioning society. People who have heard Belgian Jan Boelen speak before (either in his role as artistic director of Z33 House for Contemporary Art in Hasselt, or at the Social Design Department at the Design Academy in Eindhoven), know that he takes the freedom to speak frankly. Boelen took position by saying that he is not interested in discussing divisions between craft, design or architecture. He’d rather talk about what design – as an expanding notion – means in our daily life. Boelen points out that design used to be about offering pragmatic solutions. Today it ranges from critical and political to relational and social design. He would like to see it evolve into a design of ‘speculative narratives’. Therefore he only trusts an approach that is based on doubt. Ironically the conviction in Boelen’s voice was such that his talk felt like a manifesto, a manifesto of speculative design. What this could entail Boelen demonstrated in a tour of his recent practices as a curator around Europe. He highlighted for example the see-through church by Gijs Van Vaerenbergh in a rural region in Flanders, a project about art in the public space in cooperation with Z33. The artwork reacts to the fact that the inhabitants have a heritage of churches and burial sites to care for. This object functions as a ‘Trojan horse’ to start conversation and change, a notion Boelen would use more often. In Ljubljana, Slovenia, Boelen was curator at BIO 50, 24th Biennial of Design. In times of economic crisis designers should try and build networks and processes instead of products. A modular engine block came out of it, hacking household appliances so there is one detachable engine block powering a shaver and a kitchen machine alike. And how about a foldable house that can float in the Bosporus after an earthquake? A ‘Trojan horse’ again, helping to understand the world and offering scenarios. But not pretending to be a solution. Boelen is very suspicious of this solution thinking, also in design education. He noticed master students applying with the same ‘boring’ portfolios, offering solutions based on the same presumptions that created the problems in the first place, made with the same software even. As an encore he placed Lin Cheung’s jewellery in his initial chart. Conversation pieces he called them, that not only fall in the critical sphere but also use poetry as a strategy to pose questions about the future.

Ideas appearing through material

After all these talks, more or less deviating from the topic of the relevance of crafts, the conversation changed to materiality, when Lin Cheung was asked to be interviewed on stage by Grant Gibson. While not having many memories of artists or makers in her childhood, she went to art school nonetheless. Her BA in Brighton evolved around wood, metal, plastic and ceramics. Cheung laughs when mentioning this course, named after materials but not telling what you are supposed to do with them. It was not until her BA that she stumbled across a book, The New Jewellery by Ralph Turner, a most profound moment. ‘The key thing is’, she told Gibson, ‘I am using jewellery to explore my surroundings. It is an idea and a material coming together and then something starts making sense.’ Asked on teaching and being taught, Cheung without hesitation replies that that is how people find each other’s strengths. She recalls the artistic exchange with collegue and educator Caroline Broadhead. At the time they spoke about similarities in their processes. Instead of the phone they used email, giving them time to reflect. Still now, these conversations are with Cheung when she works, recalling answers by Broadhead as from a toolbox.

Jewellery student Viràg Motesiczky presenting the ‘trophy’ to Lin Cheung, Françoise van den Bosch Foundation chair Martijn van Ooststroom on the left. Photo: Zhi-Lang Wang

Not so sad anymore

Lin Cheung was praised by the unanimous jury (this year consisting of Evelien Bracke, Beppe Kessler, Marc Monzó,Hans Stofer and chaired by Martijn van Ooststroom) ‘for creating a model of what role jewellery can play within contemporary society’. Her work inspires younger generations as well. This was illustrated by a touching moment at the end of the programme. Cheung was presented with a piece of jewellery made by a young maker, a sympathetic tradition related to the award. Viràg Motesiczky is currently studying at the jewellery department of the Gerrit Rietveld Academie. With Not so sad anymore Motesiczky responded to the series of stone carved buttons with which Cheung recently ventilated her concern about Brexit. Motesiczky asked someone from every EU country to send in a handwritten note to Lin Cheung, along with a star-shaped button. The buttons were formed into a wreath brooch, bringing together shared feelings about the loss of a star of the European flag. Motesiczky’s piece proofed the point that craft can represent loud statements, even if small in size.

Close-up experience of Lin Cheung’s work thanks to her ‘live jewellery exhibition’. Photo: Zhi-Lang Wang

The relevance of crafts, so how about it?

Crafts recently found a favourable reception in contemporary popular culture. Today, makers play an important role. The objects they make have the power to ask questions and induce change. One of the mechanisms that makes crafts capable to do this came up in the interview with Lin Cheung herself: the immediacy of working with materials. Time and again she found that an idea started making sense ‘through the material’. If there is one thing to learn from the lectures, it is that the mastery of the craft allows for truly targeted objects.

Afterwards, the museum café was the place to continue the conversation. There, Lin’s live jewellery exhibition presented an excellent occasion to see – and feel! – her stone carved jewellery up close. This afternoon tickled not only the intellectual lobe but also the sensory system. And that is where the fascination starts.